Why Brett Donelson left the ski industry to transform girls’ lives through The Cycle Effect

Brett Donelson doesn’t consider himself an athlete.

“I like to ride bikes and run and stuff like that,” he says.

That modesty belies the fact that Donelson has been racing mountain bikes for years. He played soccer at Hobart College before becoming a competitive ski racer and a professional ski coach. He’s a certified personal trainer, USA Cycling Coach, and USA Triathlon Coach. He’s the former Cycling Director at the Athletic Club at the Westin in Avon, Colorado and the former Head Women’s Coach at Ski Club Vail.

He’s also the founder and executive director of The Cycle Effect, a nonprofit that works to provide young women equal opportunity and access to the sport of mountain biking. The program amplifies physical health and social-emotional wellbeing by helping girls develop bike skills, build self-esteem, stay engaged in school, and set goals that support their future.

Today, The Cycle Effect is thriving.

The organization provides growth opportunities and mentorship for hundreds of girls across four counties in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains. It works to remove financial barriers so girls from all backgrounds have access to the powerful life lessons that come from riding a bike. Nearly 70% of participants identify as Latinx and/or Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC).

Despite the organization’s current impact, however, the early days of developing a sports-based nonprofit were anything but easy.

“It hasn’t always been like this,” Donelson says. “It was 10 years of really hard work and solving a lot of challenges.”

We chatted with Donelson to learn more about his athletic career, The Cycle Effect, and why he left the ski industry for mountain biking — plus the pivotal mindset shifts that helped him navigate a host of challenges along the way.

Trading skis for wheels

For years, Donelson and his wife Tamara (Tam), The Cycle Effect’s co-founder, worked as ski instructors, chasing winters at renowned resorts around the globe. But in 2008, they left the ski industry.

“We were kind of disenchanted with skiing just because we were sick of being cold,” Donelson says. “And we were like, ‘What’s our next sport?’ And we jumped into [mountain bike] racing with both feet.”

At the time, Donelson also was stepping into the role of Cycling Director at the Athletic Club at the Westin. The club was making a name for itself as an elite cycling space, and it had invested in the latest indoor cycling technology and a trainer studio.

“I learned a lot about [cycling] very quickly,” Donelson says.

That learning was amplified as the Donelsons entered the world of competitive mountain bike racing. Their first year, Donelson took a back seat to support Tam’s competitive aspirations.

“It worked out really well, because she elevated herself very quickly through those ranks,” he says.

In one year, Tam scaled up from the beginner category to winning the expert category.

“And then that allowed us to ride bikes for the rest of our lives together.”

Learning to enjoy the climb

As a soccer player and a skier, Donelson was used to being the cream of the crop.

“I wasn’t really used to just being average,” he says.

So when he entered the world of competitive mountain biking, he says, “I was very concerned about what other people would think. I felt like people probably had expectations of me, or I had very high expectations of myself. I was always concerned about, ‘Who am I gonna be faster than or slower than?’ and stuff like that.”

Then Donelson turned 40. And he had what he calls a “defining moment” of clarity.

“Statistically, I’m half dead,” he realized. “That motivated me to take things a little less seriously … I just kind of realized: ‘You’re so fortunate to be able to do this.’”

Donelson started working with mindfulness coaches, who taught him to enjoy the process without fixating on the end results.

He says his mindset and his athletic career transformed when he internalized “the understanding that I truly get to choose my reaction to something … We literally have every ability to react to anything we want, however we want.”

Take a hard climb on a mountain bike, for example.

“I can make myself miserable on the climb if I want, or I can make myself be like, ‘This is sweet. I’m getting fitter. I’m prolonging my life right now’ — or whatever stories we want to tell,” Donelson says. “I’m just able to stay more focused on what’s important because I get to choose my reaction to it.”

These days, Donelson finds joy in the community he’s built around mountain bikes and racing. And he takes the competition far less seriously.

“I really learned, who cares?” Donelson says. “Let’s just go ride bikes. I still race a lot because it motivates me, but I don’t really care that much about the racing. I just like it because of the group of people. I appreciate it more; I’m more grateful for it. I truly am now just grateful to go ride my bike.”

Photo courtesy of The Cycle Effect

Growth mindset

After falling in love with biking, the Donelsons felt compelled to share the joy and growth they’d gleaned from the sport.

“We knew there were kids in our community that just didn’t have that opportunity,” Donelson says.

So when he got the chance to volunteer with a youth organization, he jumped at it. After two years of volunteering, he says, “it was clear that we should move on to create our own organization.”

And that’s exactly what they did.

In 2013, the Donelsons started The Cycle Effect.

“We started with the premise that we want to try to recruit young Latina women into our mountain bike team,” Donelson says. “And we want to give them every opportunity that they could possibly need. We wanted to really make a space that girls felt great showing up to. We also knew that if the girls do it … the whole family would get involved.”

That’s a grand vision. And in the early days, it was hard to implement.

“The amount of work was insane,” Donelson says. Both Brett and Tam worked full-time jobs while getting the program off the ground, and they faced enormous financial hurdles.

“Every week, I’d come home and put my head down and say, ‘Tam, we just can’t do this,’” Donelson recalls. “And Tam said, ‘But these girls are the only thing we talk about.’”

The love the Donelsons felt for their community kept them going through the tough times.

So did the fear of failure.

“I had so many people telling me it wasn’t possible,” Donelson says.

Companies, potential donors, former clients, even friends highlighted all the ways the program wouldn’t work.

“At the beginning, I think I just wanted to prove people wrong,” he says.

Then, Donelson’s work with mindfulness coaches led to a profound shift.

“I now have a mindset of, ‘We have no idea the amazing things that are waiting for us,’” he says. “We can sit here and talk about how many things are gonna go wrong. But we don’t even know all the things that are gonna go right when we say ‘yes’.”

So the Donelsons stayed open to their vision and to the opportunities that arose around it.

“We just kept saying ‘yes’ to the scary things that we knew we might fail at,” Donelson says. “And we were willing to say, ‘Hey, this might stop next year. But we’re gonna try this’ — whatever ‘this’ was at the time that we felt was this massive mountain.”

And more often than not, things looked pretty good from the top.

Today, The Cycle Effect directly serves more than 300 girls and young women in 5th to 12th grade, and the organization’s outreach programs have impacted more than 1,200 participants. Sixty-eight percent of those participants identify as Hispanic, Latina, or other, while 69% identify as low-income and 80% received a scholarship for the program.

Each Cycle Effect participant benefits from the organization’s three-part emphasis on physical wellness, community impact and mentorship, and building brighter futures. Participants also enjoy group and one-on-one mentoring and coaching; access to bikes, uniforms, nutritional snacks, and other gear; and a supportive community on the bike and beyond.

Before joining, 77% of participants experienced one or more life challenges, such as a lack of physical activity, high stress levels, issues with body image, challenges making friends, or bullying. Girls in the program regularly report enhanced self-confidence, increased persistence in overcoming challenges or fears, and improvements in overall health.

This growth represents the realization of the vision Donelson had from the outset.

“I just knew getting kids on bikes was a good thing,” Donelson says. “If they just show up and get on a bike, their life will be better.”

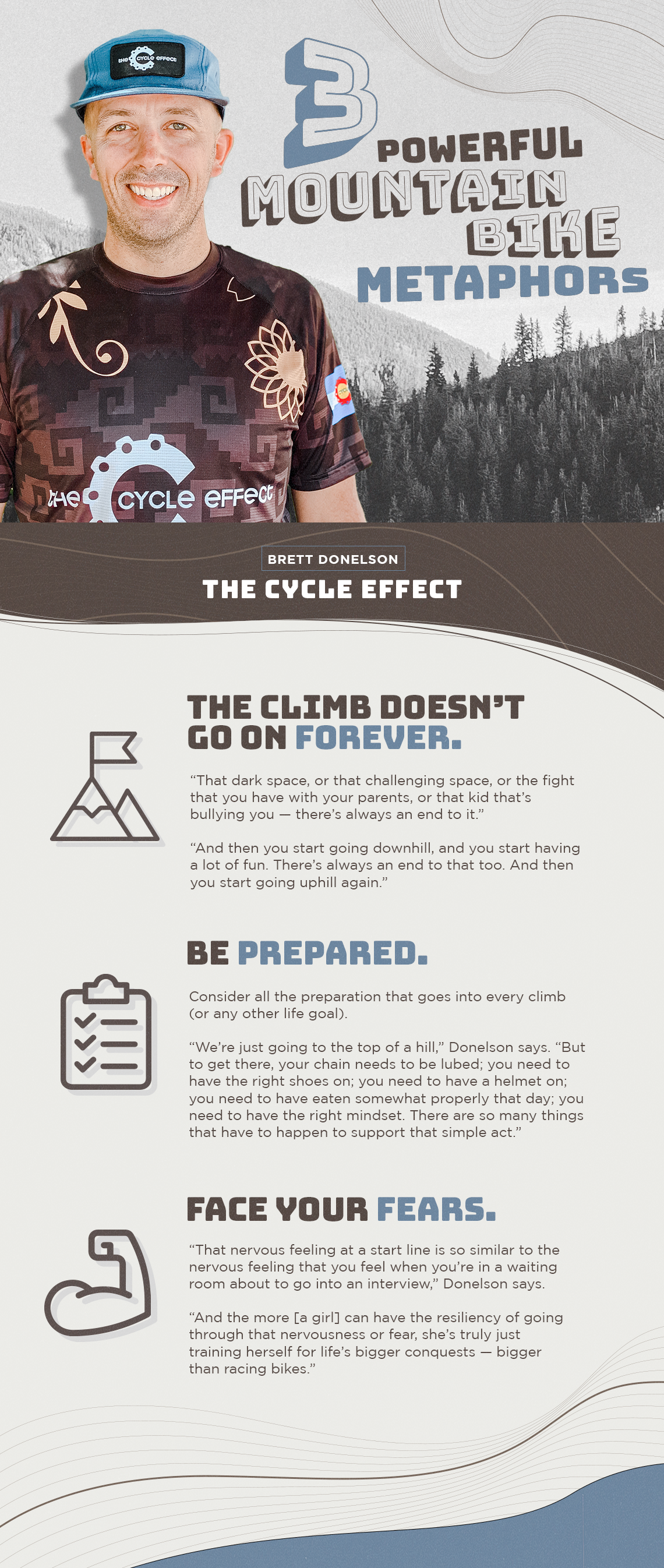

Mountain bikes and metaphors

Like Donelson, The Cycle Effect’s participants benefit from powerful life lessons through the lens of mountain biking.

“I don’t know many other sports that teach more life lessons,” Donelson says. “I think the bike as a metaphor is really, really impactful for our girls.”

For instance: “The climb doesn’t go on forever,” Donelson says. “That dark space, or that challenging space, or the fight that you have with your parents, or that kid that’s bullying you — there’s always an end to it. And then you start going downhill, and you start having a lot of fun. There’s always an end to that too. And then you start going uphill again.”

Here’s another one: Consider all the preparation that goes into every climb (or any other life goal).

“We’re just going to the top of a hill,” Donelson says. “But to get there, your chain needs to be lubed; you need to have the right shoes on; you need to have a helmet on; you need to have eaten somewhat properly that day; you need to have the right mindset. There are so many things that have to happen to support that simple act.”

And finally: “When you’re scared, getting tense and not breathing is the worst thing to do,” Donelson says. “Taking deep breaths is the way to get through it. And that doesn’t matter if it’s on a bike or if it’s for a college scholarship interview or something else.”

In fact, the Cycle Effect encourages all of its participants to race competitively for the express purpose of learning how to combat nerves.

“That nervous feeling at a start line is so similar to the nervous feeling that you feel when you’re in a waiting room about to go into an interview,” Donelson says. “And the more [a girl] can have the resiliency of going through that nervousness or fear, she’s truly just training herself for life’s bigger conquests — bigger than racing bikes.”

The Donelsons see those lessons impact girls’ lives every day.

“The confidence that they’ve learned in The Cycle Effect has allowed them to run for student government or be on committees or branch out and try different sports,” Donelson says.

Perhaps most importantly, mountain biking offers girls a chance to experience the joy that made Donelson fall in love with the sport.

“These kids are dealing with a ton,” Donelson says — whether in the form of struggles at home, bullying at school, or any number of other challenges.

But when The Cycle Effect team gives a girl a bike, teaches her to ride it, and encourages her to fly down an (appropriately sized) hill, “you can just see it in their eyes and their smiles,” Donelson says. “They haven’t had a lot of chances in their life to feel that, whatever it is — call it freedom. We can call it joy, we can call it exhilaration, whatever that emotion is that they’re feeling.”

We could call it the cycle effect.