Troy Taormina/USA TODAY Sports

In the summer of 2020 and during the Covid-19 pandemic, the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota catalyzed a wave of racial reckoning in the United States. Protesters took to the streets demanding change in the way the nation, citizens, and businesses treat people of different races and ethnicities.

From colorful caricatures to racist histories, private and public organizations reevaluated their role in perpetuating harmful stereotypes. Businesses and individuals, from the Aunt Jemima brand to the Dixie Chicks (now just the Chicks), altered such imagery and language to not reflect a harmful past.

Professional sports and sports teams were not immune to such a comprehensive and widespread movement, especially in relation to their team names and mascots. The Washington Redskins of the NFL were first to grapple with their fate. After years of debate, the movement initiated an almost immediate name change in response to sponsor backlash in light of the cultural shift. The Washington Redskins became the Washington Football Team.

The Cleveland Indians of Major League Baseball were next. Just a few years after dropping the Chief Wahoo logo, Cleveland began the process of establishing a new name — one free of Native American imagery. The Cleveland Guardians came to fruition in 2021.

Two big sports franchises remain to evaluate their role in perpetuating stereotypes: NFL’s Kansas City Chiefs and MLB’s Atlanta Braves. Of these two, the Braves stand out for their consistent Native imagery, particularly one tradition that occurs hundreds of times every season.

What is the Braves’ tomahawk chop?

In almost every home game since 1991, a drum beat, organ, or whistle has led the crowd in a “war chant” and subsequent hinged chopping motion to cheer on the Atlanta Braves. The prelude to the chant plays during longer intermissions, such as a pitching change, long at-bat, or home run.

The tomahawk chop is not unique to Atlanta, but it has been held as a tradition at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, Turner Field, and recently Truist Park. Depicted prominently on jerseys and encouraged via a foam tomahawk form, the tomahawk and its chop are synonymous with the Atlanta Braves.

What is the origin of the tomahawk chop?

For Native American imagery, Florida State University reigns supreme. The FSU Seminoles hold claim to many of the original chants and cheers associated with Native peoples; the tomahawk chop “war chant” is no different.

Legend has it that the Braves’ style of “war chant” was started by a few members of the Theta Chi fraternity in 1983. The Florida State band played several songs mimicking American Indians, such as “Massacre”. These songs were not original during the time, as schools such as the University of Illinois played these tunes for years.

During one football game in 1983, a fraternity brother decided to join in and belted a melody to match. Soon enough, the fraternity taught the new lyrics and song to many others, including the “Scalphunters,” a booster group on campus, and FSU’s band, the “Marching Chiefs.” The fraternity continued to spread and bolster the use of the chant by spontaneously adding a chopping motion, one quickly adopted by many at the football games. Meanwhile, the band honed their “War Chant” music to better fit the new melody and demonstrated it during the 1986 game against Auburn. To the giddiness of the fans, the band perfectly matched the melody of the chant, and the chop motion followed.

Further analyses complicate this legend.

According to several sources, the new music most resembled the 1950s Pow-wow cartoon. “Pow-wow the Indian Boy” aired for years in the 1950s, but the connection was never discovered until 1993 by an Atlanta Journal-Constitution reader, Jane Hammond. Tom Kacich of the Champaign (Ill.) News-Gazette claims to have noticed the similarities later on in 2017 when writing about the University of Illinois’s removal of the “War Chant” from its football games.

Regardless of the exact origin of the “War Chant” music, the reality remains the same — it hardly depicts the real music of the area’s Native people. Critics blast this discrepancy as dehumanizing the imagery and likeness of the Native people, while defenders reason that it is most similar to Hollywood’s portrayal of the Native American community during that time.

When did the Braves adopt the chop in Atlanta?

Organist Carolyn King Jones, the first black female organist in the MLB, originally thought that the song matched what would be expected at a game for a team called the Braves. She learned it years prior in a songbook and played it a few times in 1990.

In the 1991 season, the Florida State three-sport superstar Deion Sanders signed to play in Georgia on the roster for the Braves. Consequent to his plate appearance, the Braves fans broke out in unison the “War Chant” of FSU. Fans continued to engage in the chop all season, prompting protests at their World Series appearance. Nonetheless, from that season, the chop stuck.

Upon her retirement in 2004, Jones reflected on her legacy and the chop. She spoke about her age and immaturity at the time, unaware of the implications this song would have on the Native American community. In speaking to one of the protesting Chiefs, he responded to take care of herself and her family as the Braves organization would find someone to play the song if she were to step down.

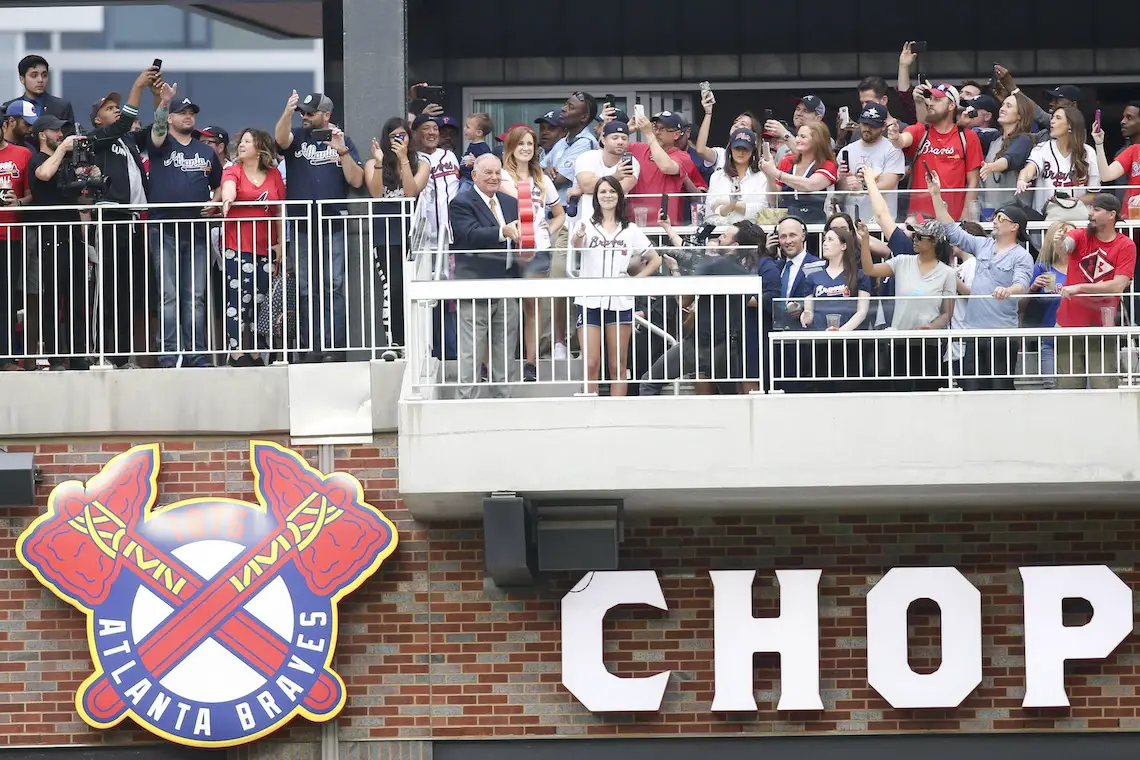

Former Atlanta Braves manager Bobby Cox does the Tomahawk Chop against the Philadelphia Phillies in the first inning at SunTrust Park, in March of 2018.

Brett Davis/USA TODAY Sports

1991 protests

During the 1991 World Series, about 150 protesters from the American Indian Movement showed up outside of the stadium in Minneapolis. Their overarching perspective showed disdain for the Atlanta Braves organization and Major League Baseball, calling the false images of American Indians “pure ignorance.” They called for the abolishment of the chop, a change to the Braves name, and tempering of Braves fans.

In response, both former MLB Commissioner Fay Vincent and former Braves president Stan Kasten deferred conversations surrounding Native American imagery to after the World Series concluded; neither made public comments about the issue afterward. Others in the Braves’ organization called the chop a form of unification and family. The Braves went on to lose the World Series 4-3.

Modern engagement of the tomahawk chop

During the 2019 season, the Braves played the St. Louis Cardinals in the National League Division Series. Cardinals pitcher Ryan Helsley criticized the chop and Native American mascots, which he described as “disappointing,” “disrespectful,” and “a misconception of [Native Americans].” Helsley, who is a member of the Cherokee Nation, called for the Braves to end the tomahawk chop. The Braves responded by discouraging the chop when Helsley was on the mound and halting the distribution of foam tomahawks. Outside of those innings and without foam tomahawks, the chop persisted.

Discussion surrounding the Braves’ harmful imagery continued over the years, but louder calls for its removal stirred up after the Washington Football Team and Cleveland Guardians engaged in discussion about their former names (Redskins and Indians, respectively) during the summer of 2020. Both moved on from their representation of Native Americans.

In response to wide pressure to address the issue, the Atlanta organization established the Native American Working Group and partnered with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI). Though the EBCI derived some benefit in the success of the Braves through their sponsorship, Chief Richard Sneed still criticized the chop and associated music as “just so stereotypical, like old-school Hollywood. Come on, guys, it’s 2020. Move on. Find something new.” The working group suggested that the Braves relax their emphatic support of the chop, relying on visual cues and a drum or whistle to start the chop. The Braves implemented these changes during the 2021 season.

2021 World Series

Calls for moving on from the chop intensified leading up to the Braves’ appearance in the 2021 World Series.

Prior to the first game, MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred established support of the chop based on the Braves’ engagement with the Native American community, seemingly referring to the EBCI. He continued that the Native peoples seemed to fully support the Braves and their chop.

In a stark rebuttal of Manfred’s comments, the National Congress of American Indians published a statement reiterating their condemnation of the Braves’ chop, false Native imagery, and name. The NCAI refuted the idea that because the Braves developed a relationship with local tribes, they are permitted to continue to misrepresent Native culture. They argued that because networks widely televise the World Series, it removes the borders of impact, affecting the Native American groups across the country and Native peoples around the world.

Previous Braves logo controversy

The chop is not the only controversy in the Atlanta Braves past.

The Braves’ logo contained a screaming American Indian from 1966 to 1989. The organization almost reintroduced it for nostalgia during spring training in 2013 but pulled it due to massive backlash.

More famously, from 1966 until 1985, Chief Noc-A-Homa held the mascot position for the Braves. Before each Braves game, he would lead a dance on the pitcher’s mound before returning to his teepee in the stands.

The person behind the mascot from 1969 to its retirement in 1985 was Levi Walker, Jr. He theorized that if the Braves were to promote a caricature of an American Indian, they “ought to have an Indian” playing the part. Walker, who is a member of the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa, approached the Braves and won the job in 1969.

From his perspective, the names “Braves” and “Indians” honor the Native American community, though he feels differently about the name “Redskins.” Of his tribe, he estimates around 80 percent respect the Braves’ organization while the rest do not agree with its use of a caricature of Native culture as a mascot.

This sentiment resounds in the larger debate around the Braves. While other organizations have altered their imagery in response to the overwhelming push for change, the Braves have continued to support the tomahawk chop and other symbols, though less emphatically than before. The Braves organization and supporters believe that they are honoring the Native people that once occupied the land the Braves now represent. Critics claim that these images do nothing but promote dehumanizing and antiquated images of Native people.

During the 2021 Championship season, the players seemed to want to take the chop in a different direction: their uniform celebration after big hits was a sideways chop as if cutting down a tree. Perhaps the use of this celebration will encourage other demonstrations of the chop other than the infamous and controversial tomahawk chop and “war chant.” Moving on would allow the celebration of the Braves for all they have achieved, unclouded by a controversial and persistent present and despite a colored past.