Photo credit: Paul Robert, Creative Commons

Nestled high in the mountains outside of Budapest, the Hungarian water polo team could only watch as plumes of smoke that rose in the distance marked the beginning of a revolution.

A battle for freedom raged on below as their countrymen clashed with communist forces that had invaded their country. As Russian tanks rode through the streets of Budapest, they would be on a journey to defend their gold medal, the fate of their loved ones remaining a desperate mystery.

Nearly 3,000 people died in a single day. On Nov. 4, 1956, the student-led protest that had turned into an armed rebellion was brutally crushed by a wave of overwhelming firepower. A thousand tanks and 200,000 Russian troops supported by MIG fighter jets brought a sudden and violent end to the 1956 Hungarian Revolution.

But for the Hungarian water polo team, the fight wasn’t over yet.

Just over a month later, Hungary would again take on the Russians. This time in the most brutal water polo match in Olympic history. Pent-up anger and aggression from both sides would spill out and turn a 4-0 lopsided Hungarian victory into the “Blood in the Water” match.

What happened leading up to the Hungarian Revolution?

The tensions that led to the 1956 Hungarian Revolution began in the aftermath of World War II. Once allies against the Nazis, the Soviet Union and the West were now engaged in a power struggle, and unwitting Hungary (who had a complicated relationship with Nazis and ended up on the losing the side of the war) became a pawn in this global chess match.

As the war was drawing to a close, Great Britain made an agreement with Joseph Stalin to turn the dominant control of Hungary, along with several other Eastern European countries, over to the Soviet Union. This agreement would establish the Eastern bloc and embroil the world in a decades-long Cold War.

Just two years after the 1944 agreement that essentially forced Hungary into the USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics), the communist takeover of Hungary began.

Unsatisfied with the results of the previous year’s democratic, multi-party election, the Hungarian Communist Party (HCP), backed by the Soviet Union, used its power to “correct” the outcome and place its members in influential political roles.

The HCP then used this ill-gotten power to dismantle their opposition through the arrest and expulsion of non-conforming political leaders, mostly members of the popular Independent Smallholders’ Party that had actually won the election with nearly 60% of the vote.

By 1948, only the Hungarian Communist Party remained. In just four years, Hungary was transformed by corruption and abuse of power from a multi-party, democratic country to a single-party communist nation.

To further cement the Soviet’s grip on Hungary, a new constitution with stringent adherence to communist policies was ratified in August 1949.

In the following five months, banking and industry were nationalized and peasants were forced to collective farms. By December of that year, 99% of the workforce was toiling away for the State.

How did the death of Stalin impact the Hungarian Revolution?

For the next five years, the citizens of Hungary lived as powerless denizens under the iron-fisted rule of Joseph Stalin. Only his death in 1953 would loosen the grip he held over the human spoils of his WWII victory.

Following the death of Stalin, the new communist regime, led by Nikita Khrushchev, pulled back on strict communist policies, and a new prime minister, Imre Nagy, was installed in Hungary.

The new leader de-privatized collective farms, canceled enforced quotas on production and raised the price the government would pay for commodities. These policies ultimately failed and Nagy was forced to resign in 1955, but it was a move toward a more free Hungary.

A secret speech that changed the world

The dismantling of Stalin’s policies would go even further after a world-changing speech by Nikita Khrushchev in February 1956.

Known as the “secret speech,” Khrushchev outlined many of the atrocities of Stalin, including the imprisonment of thousands of political prisoners in gulags. This speech broke the spell of propaganda Stalin had over the people of the USSR. Stalin became an enemy of the people who once adored him. Their protector became the one who had abused them.

Formally titled On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences, Khrushchev’s speech was never meant to be seen by the West.

However, copies of the speech distributed to communist parties of different Soviet satellite states passed from Israeli intelligence into the hands of the CIA. It was then printed in English and American newspapers.

The De-Stalinization of Hungary

The revelations of Khrushchev’s speech led to fervent disdain for Stalin. Once held up as a god of sorts, his statues were pulled to the ground all over the USSR.

This anti-Stalin sentiment emboldened countries like Hungary to take further steps away from communism.

By October 1956, anti-Soviet protests were widespread across the region.

Photo credit: DaveLevy, Creative Commons

The 1956 Hungarian Revolution prior to the Blood in the Water match

While statues of Stalin were dragged through the streets, a once peaceful protest turned violent as demonstrators went from shouting at Soviet occupying forces to throwing Molotov cocktails at them.

Open fighting broke out in Hungary’s capital city of Budapest on Oct. 23, 1956. The meagerly armed Hungarians won the first phase of fighting, and a more democratically aligned leader, former prime minister Imre Nagy, replaced Mátyás Rákosi, a strict Soviet loyalist who, since 1948, had taken hundreds of political prisoners while murdering thousands more.

As the newly appointed leader, Nagy worked to reestablish a multi-party democratic government and actually made headway with Russia on negotiations over the occupation of Hungary.

But on Nov. 1, he took it too far by declaring Hungarian neutrality and attempting to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact, a collective USSR defense treaty.

Three days later, on Nov. 4, 1956, 200,000 Russian troops poured across the border, flanked by a thousand Soviet tanks with MIG fighter jets providing air support.

The 1956 Hungarian revolution ended with a devastating crackdown. Thousands of citizens were slaughtered in the streets as explosions decimated the city. Nearly 3,000 Hungarian civilians were killed by Soviet troops in a single day. Another 20,000 were wounded. The death toll continued to climb in the following weeks.

The West admonished the actions of the Soviet Union, but was too distracted by the Suez Canal Crisis (a complicated, concurrent diplomatic matter that many believed threatened world peace) to offer any real support. Plus, their association with the Nazis didn’t engender much sympathy.

Imre Nagy was deposed as prime minister of Hungary and later arrested and executed in 1958.

The Hungarian water polo team leading up to the 1956 Melbourne Olympics

As their countrymen waged battle for freedom below, the Hungarian water polo team was secluded high in the mountains in a training facility outside the city of Tata.

The pride of a nation, the Hungarian water polo team had won the gold medal in the 1952 Olympic Games in Helsinki, Finland, and were now preparing to defend their title at the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne.

The Hungarian water polo team, known as the Magyars (after early settlers of Hungary), dominated water polo in the 20th century, winning a medal at every Olympic Games from 1928 to 1980. But no victory would be more meaningful than the one that came on Dec. 6, 1956, just one month after the Soviet onslaught.

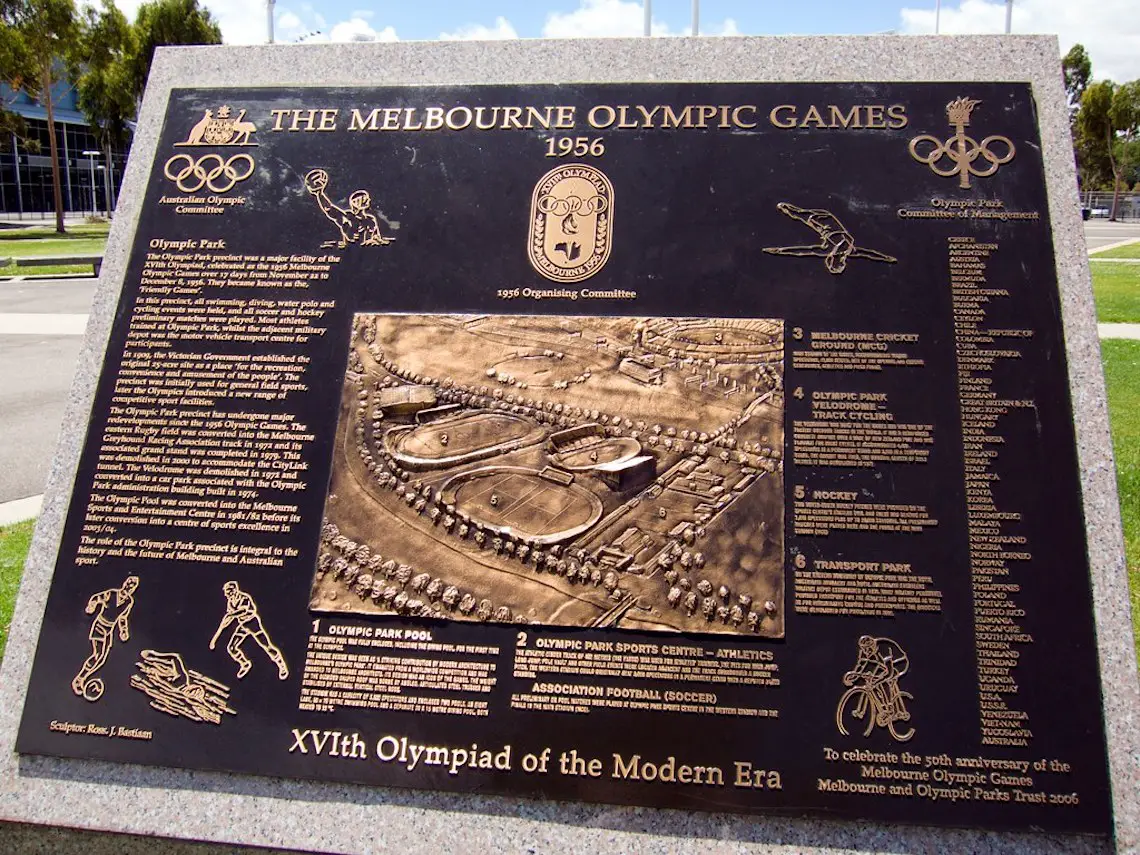

The first Olympic Games held in the Southern Hemisphere

The 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games were the first held outside of Europe or North America and the first Olympics to take place in the Southern Hemisphere.

Due to the nature of the seasons, the games were held in November and December and would be the only Summer Games ever held in those months.

The Hungarian water polo team arrives at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics

A famous gold medal-winning water polo player and captain of the Hungarian team, Dezső Gyarmati was also highly involved in politics. He trained during the day and worked to help the revolution during the night.

He used his status to go straight to Imre Nagy and secure passports and exit visas for the team. After the outbreak of fighting in Budapest, Hungarian officials were able to usher the water polo team to Czechoslovakia. From there, they began their journey to Australia.

In an interview with Reuters, Gyarmati recalled, “We had to fly from Prague as no airline would land in Budapest. We were in midair to Melbourne when the pilot told us the news Soviet tanks had invaded Budapest. We knew they would drown the revolution in blood.”

Due to the ongoing Suez Canal Crisis, it took several days to arrive in Australia, and with limited access to news, the water polo team was unaware of the ultimate outcome of their country’s fight for freedom. They only knew it would be bad and wouldn’t learn of the extent of the tragedy until they finally landed in Melbourne.

Filled with anger and shock at the death and destruction at the hands of the Soviets, and like their counterparts at home, the water polo team immediately focused their rage on symbols of the Soviet occupation.

Just as protestors in Budapest tore down and defaced the ubiquitous red stars of Communism, they tore down Hungarian flags emblazoned with Communist insignia and raised the banner of a Free Hungary.

They had a new purpose at the games now. They had to stand for the pride of their country.

A water polo rivalry between Hungary and Russia

Hungarian dominance in the sport of water polo had long been a thorn in the side of the Russians. Already long-standing rivals in both politics and sports, things became even more personal in the years leading up to the 1956 Olympics.

Embarrassed by not medaling in the 1952 games (while Hungary won gold), the Russians exerted their power to come train and scrimmage at the Hungarian water polo facility. While some players formed tenuous cross-team friendships, the familiarity bred an underlying hostility that stirred under the surface.

This only added to the animosity unleashed on Dec. 6, 1956—barely a month after the Russian invasion of Hungary.

The road to the Blood in the Water match

Led by Olympic champion Dezső Gyarmati, an ambidextrous hulk of a man widely considered the greatest water polo player of all time, the Hungarians made it through the group stage of the 1956 Melbourne Olympics water polo tournament with a record of 2-0 after easily beating Great Britain (6-1) and the United States (6-2) with a combined 12-3 goal advantage.

Following suit, the Soviet Union also made it through the preliminary group round, but without near the dominance of the Hungarians. The Russians went 2-1 with only a three-goal advantage, losing to eventual silver medal-winning Yugoslavia 2-3, beating Romania by a score of 4-3 and defeating home country Australia 3-0.

Note: Hungary’s Group B only contained three teams while Russia’s Group A contained four teams, hence the difference in games played in the opening round.

Hungary continued its domination in subsequent rounds, defeating both Italy and Germany 4-0 while the Soviet Union defeated Italy 3-2 and the United States 3-1. The two nations were now set on a collision course to meet in the semi-final round.

And a collision it certainly was. Thanks to a barrage of skirmishes, it would be the most brutal confrontation in modern Olympic history.

The Blood in the Water match on Dec. 6th, 1956

With emotional wounds still fresh from Russia’s brutal invasion of their homeland, the bloody battle moved from the streets of Budapest to the Olympic pool.

But this time, the sides were even. No tanks, no bombs, no missiles. Only hands, knees and elbows in the semi-final match of the 1956 Melbourne Olympics.

It was merciless and violent from the start.

The Hungarian captains refused to shake hands with the Russians. Not long after the opening whistle, Hungarian team captain Gyarmati broke the nose of Russian team captain, Petre Mshvenieradze. Once Mshvenieradze got back in the pool, Gyarmati went after him again and hit him once more across his already broken nose.

The brutality never stopped.

Hungary had a strategy to provoke the Russian team through constant physical and verbal assaults. Having been taught the Russian language in school, they were adept at hurling insults. It worked, and the Soviet team returned the favor.

Both teams took every chance possible to inflict pain and punish their opponents, even holding each other’s heads underwater. The injuries became numerous as the match played on. Five players were ejected from the match and forced to exit the pool.

The violence came to a head with 60 seconds left in the match. Distracted by a whistle, Hungarian player Ervin Zádor turned to look at the referee.

That’s when Soviet player Valentin Prokopov, who Zádor admits to have been trying to provoke, reared back and threw a cheap shot to the side of Zádor’s head, creating a cut above his eye that sent blood spilling down the side of his face.

In Zádor’s words: “I saw about 4,000 stars. And I reached to my face and I felt warm blood pouring down.”

In a separate interview for the film Freedom’s Fury, a 2006 movie based on the match, Zádor said, “I shouldn’t have taken my eye off Prokopov. The next thing I saw, he had his full upper body out of the water and he was swinging at my head with an open arm.”

The sucker punch set off a near-riot among the 5,000 spectators in the stands. Many of them were immigrants from Hungary who had come to watch their national heroes.

As the enraged crowd began to scale barriers and rush the pool, referees called the match. Australian police quickly escorted the Russian team to the locker rooms.

Gyorgy Karpati, who scored a goal for Hungary during the match, later told The Associated Press, “I have to admit that I’m convinced even the referee was pulling for us. We were from a small country battling the huge Soviet Goliath.”

The 1956 Hungarian water polo team win Olympic gold

The only overwhelming force that day was Hungary. They dominated Russia with a final score of 4-0.

In the record book, it simply went down as another victory for the Hungarians. But in the annals of history, it went down as the “Blood in the Water” match thanks to an iconic image of Ervin Zádor as he exited the swimming pool with blood streaming down his face.

The victorious Hungarians went on to defeat Yugoslavia 2-1 in the gold medal match to win the second of what would be three gold medals, along with a silver and bronze, en route to medaling in five consecutive Olympics.

It was complete domination for the Magyars of Hungary in the 1956 Summer Olympic Games. They went 5-0 with an overall goal advantage of 20-3.

The Cold War and the 1956 Melbourne Olympics

By 1956, the Cold War was in full swing and the international gathering at the 1956 Summer Olympics was crawling with spies from the East and West.

Although the CIA was barred from the games, American secret agents posing as media members helped 46 members of the Hungarian Olympic team defect to the West, along with nearly half of the water polo team, including captain Dezső Gyarmati and the soon-to-be-famous Ervin Zádor.

1956 Hungarian water polo player, Ervin Zádor, settles in California

Though he wishes he were more remembered for his incredible water polo player talent, Ervin Zádor is most remembered as the bloody icon for his appearance on the cover of Time magazine.

But, after refusing to return to Hungary and defecting to the West, he also established quite a post-Olympic career. After settling in Linden, California, Zádor became a very successful swimming instructor, coaching nine-time Olympian Mark Spitz as a teenager.

Zádor ran the Aquatics programs at the Ripon Aquatics Center until he passed away in 2012. During that time, he created the Zador Rebound Board, which has become an essential training tool for top-ranked collegiate water polo programs at schools like Stanford University and the University of Southern California (USC).

His water polo legacy is now carried on by his children. His son, Erik, took over the Ripon Aquatics Center, which is now known as the Zador Memorial Aquatics Center, and took his first athlete to the Olympic trials in 2017.

Zádor’s daughter, Christine, carved her own path in water polo as a two-time high school All-American and NCAA national champion at USC. In 2007, she founded Zador Aquatic Supply which is now known as Zaqua.

In 2017, Erik and Christine traveled to Budapest to compete at the FINA World Masters Championships.

The Blood in the Water match in film

The Blood in the Water match was documented in a film called Freedom’s Fury. Released in 2006 for the 50th anniversary of the match, it was co-executive produced by Lucy Liu and Quentin Tarantino. Freedom’s Fury is narrated by Ervin Zádor’s famed protege, Mark Spitz.

During the production of the film, which took five years to complete, writer and director Colin Gray brought together eight Hungarian players and four ex-Soviet players. In an interview with The Associated Press, he noted that he was struck by the shared humanity that emerged during the reunion.

“These guys were able to finally reconnect as human beings and as fellow athletes. That was something that we really wanted to highlight, the sort of humanistic side to counter the sort of oppression of ideology that everyone had suffered under in the Eastern bloc.”

The legacy of the Blood in the Water Match

The 1956 Hungarian water polo team stood for more than gold at the podium that year. They stood for the constant struggle against oppression.

While this is often an unfair fight, sports allow for a level playing field where a little bit of hope can grow in the face of overwhelming force. The 1956 Hungarian water polo team could never reverse the devastating tide of destruction that overtook their country on Nov. 4, 1956, but they did give their native homeland a reason to hold its head high with pride.

The last remaining member of the 1956 Hungarian water polo team died in June of 2020.

Photo credit: “Plaque Commemorating the 1956 Olympic Summer Games” by Paul Robert Lloyd is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Photo credit: “The Hungarian Revolution” by DaveLevy is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0